Horizontal Communication

Horizontal Information Sharing and Collaboration

Horizontal communication overcomes barriers between departments and provides opportunities for coordination and collaboration among employees to achieve unity of effort and organizational objectives.

- Collaboration

Collaboration means a joint effort between people from two or more departments to produce outcomes that meet a common goal or shared purpose and that are typically greater than what any of the individuals or departments could achieve working alone.

To understand the value of collaboration, consider the 2011 U.S. mission to raid Osama bin Laden’s compound in Pakistan. The raid could not have succeeded without close collaboration between the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA)Opens in new window and the U.S. militaryOpens in new window.

There has traditionally been little interaction between the nation’s intelligence officers and its military officers, but the war on terrorism has changed that mindset.

During planning for the bin Laden mission, military officers spent every day for months working closely with the CIA team in a remote, secure facility on the CIA campus. “This is the kind of thing that, in the past, people who watched movies thought was possible, but no one in the government thought was possible,” one official later said of the collaborative mission.

- Horizontal Linkage

Horizontal linkage refers to communication and coordination horizontally across organizational departments.

Its importance is articulated by comments made by Lee Iacocca when he took over Chrysler Corporation in the 1980s. The following quote might be three decades old, but it succinctly captures a problem that still occurs in organizations all over the world:

What I found at Chrysler were thirty-five vice presidents, each with his own turf. … I couldn’t believe, for example, that the guy running engineering departments wasn’t in constant touch with his counterpart in manufacturing. But that’s how it was. Everybody worked independently. I took one look at that system and I almost threw up. That’s when I knew I was in really deep trouble. … Nobody at Chrysler seemed to understand that interaction among the different functions in a company is absolutely critical. People in engineering and manufacturing almost have to be sleeping together. These guys weren’t even flirting!

During his tenure at Chrysler, Iacocca pushed horizontal coordination to a high level. All the people working on a specific vehicle project—designers, engineers, and manufacturers, as well as representatives from marketing, finance, purchasing, and even outside suppliers—worked together on a single floor so they could easily communicate. Horizontal linkage mechanisms often are not drawn on the organization chart, but nevertheless are a vital part of organization structure. Small organizations usually have a high level of interaction among all employees, but in a large organization such as Chrysler, Microsoft, or Toyota, providing mechanisms to ensure horizontal information sharing is critical to effective collaboration, knowledge sharing, and decision making. For example, poor coordination and lack of information sharing has been blamed for delaying Toyota’s decisions and response time to quality and safety issues related to sticky gas petals, faulty brakes, and other problems. The following devices are structural alternatives that can improve horizontal coordination and information flow. Each enables people to exchange information.

- Information Systems

A significant method of providing horizontal linkage in today’s organizations is the use of cross-functional information systems. Computerized information systems enable managers or frontline workers throughout the organization to routinely exchange information about problems, opportunities, activities, or decisions. For example, at Veterans Administration (VA) hospitals around the country, a sophisticated system called Vista enables people all across the organization to access complete patient information and provide better care. By enabling close coordination and collaboration, technology helped transform the VA into one of the highest-quality, most cost-effective medical providers in the United States.

Some organizations also encourage employees to use the company’s information systems to build relationships all across the organization, aiming to support and enhance ongoing horizontal coordination across projects and geographical boundaries. CARE International, one of the world’s largest private international relief organizations, enhanced its personnel database to make it easy for people to find others with congruent interests, concerns, or needs. Each person in the database has listed past and current responsibilities, experience, language abilities, knowledge of foreign countries, emergency experiences, skills and competencies, and outside interests. The database makes it easy for people working across borders to seek each other out, share ideas and information, and build enduring horizontal connections.

- Liaison Roles

A higher level of horizontal linkage is direct contact between managers or employees affected by a problem. One way to promote direct contact is to create a special liaison role.

- A liaison person is located in one department but has the responsibility for communicating and achieving coordination and collaboration with another department.

- Liaison roles often exist between engineering and manufacturing departments because engineering has to develop and test products to fit the limitations of manufacturing facilities.

An engineer’s office might be located in the manufacturing area so the engineer is readily available for discussions with manufacturing supervisors about engineering problems with the manufactured products. A research and development person might sit in on sales meetings to coordinate new product development with what sales people think customers are wanting.

- Task Forces

Liaison roles usually link only two departments. When linkage involves several departments, a more complex device such as a task force is required.

A task force is a temporary committee composed of representatives from each organizational unit affected by a problem.

Each member represents the interest of a department or division and can carry information from the meeting back to that department.

Task forces are an effective horizontal linkage device for temporary issues. They solve problems by direct horizontal collaboration and reduce the information load on the vertical hierarchy. Typically, they are disbanded after their tasks are accomplished.

Organizations have used task forces for everything from organizing the annual company picnic to solving expensive and complex manufacturing problems. One example comes from Georgetown Preparatory School in North Bethesda, Maryland, which used a task force made up of teachers, administrators, coaches, support staff, and outside consultants to develop a flu preparedness plan. When the H1N1 flu threat hit several years ago, Georgetown was much better equipped than most educational institutions to deal with the crisis because they had a plan in place.

Relational Coordination

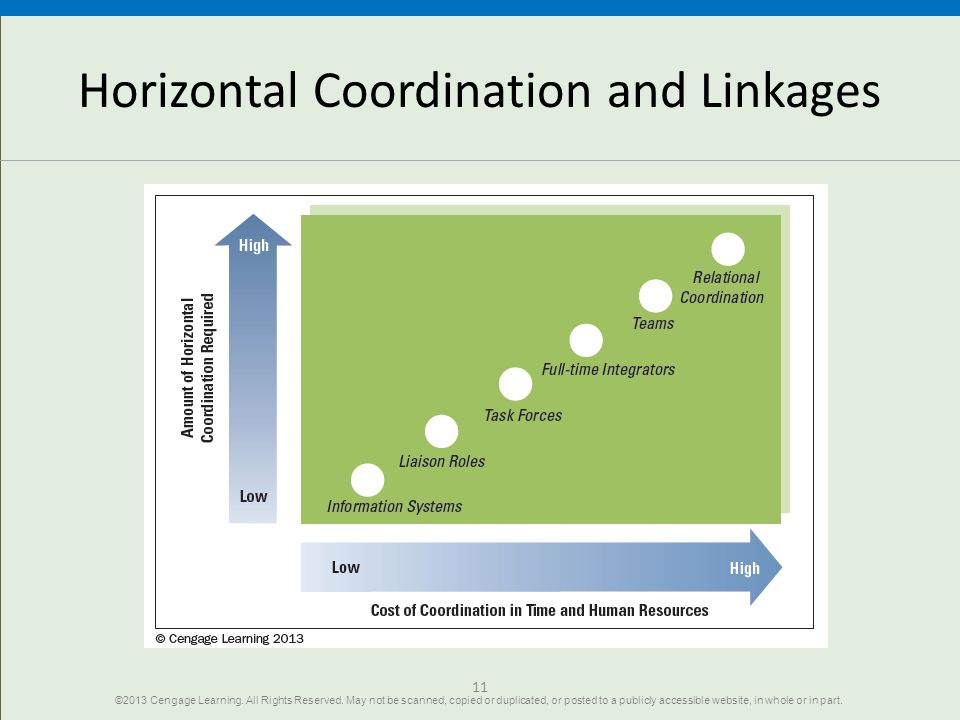

The highest level of horizontal coordination illustrated in Figure X-4 is relational coordination.

Relational coordination refers to “frequent, timely, problem-solving communication carried out through relationships of shared goals, shared knowledge, and mutual respect.”

Relational coordination isn’t a device or mechanism like the other elements listed in Figure X-4, but rather is part of the very fabric and culture of the organization.

Figure X-4 Ladder of Mechanisms for Horizontal Linkage and Coordination | Credit — ResearchGate Opens in new window

Figure X-4 Ladder of Mechanisms for Horizontal Linkage and Coordination | Credit — ResearchGate Opens in new window

In an organization with a high level of relational coordination, people share information freely across departmental boundaries, and people interact on a continuous basis to share knowledge and solve problems. Coordination is carried out through a web of ongoing positive relationships rather than because of formal coordination roles or mechanisms. Employees coordinate and collaborate directly with each other across units.

Building relational coordination into the fabric of the organization requires the active role of managers. Managers invest in training people in the skills needed to interact with one another and resolve cross-functional conflicts, build trust and credibility by showing they care about employees, and intentionally foster relationships based on shared goals rather than emphasizing goals of the separate departments. People are given freedom from strict work rules so they have the flexibility to interact and contribute wherever they are needed, and rewards are based on team efforts and accomplishments. Frontline supervisors have small spans of control so they can develop close working relationships with subordinates and coach and mentor employees. Managers also create specific cross-functional roles that promote coordination across boundaries.

| Remember This |

|---|

|

The input of sales personnel and top management is essential to the sales forecast. In small companies the budgeting process is often informal. In larger companies, a budget committee has responsibility for coordinating the preparation of the budget. The committee ordinarily includes:

- the president,

- treasurer,

- chief accountant (controller), and

- management personnel from each of the major areas of the company, such as sales, production, and research.

The budget committee serves as a review board where managers can defend their budget goals and requests. Differences are reviewed, modified if necessary, and reconciled. The budget is then put in its final form by the budget committee, approved, and distributed.

| Business Often Feel Too Busy to Plan for the Future |

|---|

| A study by Willard & Shullman Group Ltd, found that fewer than 14% of businesses with less than 500 employees do an annual budget or have a written business plan. For many small businesses the basic assumption is that, “As long as I sell as much as I can, and keep my employees paid, I’m doing OK.” A few small business owners even say that they see no need for budgeting and planning. Most small business owners, though, say that they understand that budgeting and planning are critical for survival and growth. But given the long hours that they already work addressing day-to-day challenges, they also say that they are “just too busy to plan for the future.” |

Budgeting and Human Behavior

A budget Opens in new window can have a significant impact on human behavior. It may inspire a manager to higher levels of performance. Or, it may discourage additional effort and pull down the morale of a manager.

Why do these diverse effects occur?

The answer is found in how the budget is developed and administered.

In developing the budget, each level of management should be invited to participate. This bottom-to-top approach is referred to as participative budgeting. The advantages of participative budgeting are:

- First, that lower-level managers have more detailed knowledge of their specific area and thus are able to provide more accurate budgetary estimates.

- Second, when lower-level managers participate in the budgeting process, they are more likely to perceive the resulting budget as fair.

The overall goal is to reach agreement on a budget that the managers consider fair and achievable, but which also meets the corporate goals set by top management.

When this goal is met, the budget will provide positive motivation for the managers. In contrast, if the managers view the budget as being unfair and unrealistic, they may feel discouraged and uncommitted to budget goals.

The risk of having unrealistic budget is generally greater when the budget is developed from top management down to lower management than vice versa.

Participative budgeting does, however, have potential disadvantages.

First, it is more time-consuming (and thus more costly) than a top-down approach, in which the budget is simply dictated to lower-level managers.

A second disadvantage is that participative budgeting can foster budgetary gaming through budgetary slack.

Budgetary slack occurs when managers intentionally underestimate budgeted revenues or overestimate budgeted expenses in order to make it easier to achieve budgetary goals.

To minimize budgetary slack, higher-level managers must carefully review and thoroughly question the budget projections provided to them by employees whom they supervise. For the budget to be effective, top management must completely support the budget. The budget is an important basis for evaluating performance. It also can be used as a positive aid in achieving projected goals.

The effect of an evaluation is positive when top management tempers criticism with advice and assistance. In contrast, a manager is likely to respond negatively if top management uses the budget exclusively to assess blame. A budget should not be used as a pressure device to force improved performance. In sum, a budget can be a manager’s friend or a foe.

Budgeting and Long-Range Planning

Budgeting and long-range planning are not the same. One important differences is the time period involved.

- The maximum length of a budget is usually one year, and budgets are often prepared for shorter periods of time, such as a month or a quarter.

- In contrast, long-range planning usually encompasses a period of at least five years.

A second significant difference is in emphasis.

- Budgeting focuses on achieving specific short-term goals, such as meeting annual profit objectives.

- Long-range planning, on the other hand, identifies long-term goals, select strategies to achieve those goals, and develops policies and plans to implement the strategies.

In long-range planning, management also considers anticipated trends in the economic and political environment and how the company should cope with them.

The final difference between budgeting and long-range planning relates to the amount of detail presented.

- Budgets can be very detailed.

- Long-range plans contain considerably less detail.

The data in long-range plans are intended more for a review of progress toward long-term goals than as a basis of control for achieving specific results. The primary objective of long-range planning is to develop the best strategy to maximize the company’s performance over an extended future period.

You Might Also Like:

- Research data for this work have been adapted from the manual:

- Organization Theory & Design By Richard L. Daft