Short-Term versus Long-Term Budgets

Most organizations have annual budgeting processes. Starting in the prior year, organizations develop detailed plans of how many units of each product they expect to sell, at what prices, the cost of such sales, and the financing necessary for operations .

These budgets then become the internal “contracts” for each responsibility center (cost, profit, and investment center) within the firm. These annual budgets are short term in the sense that they only project one year at a time. But most firms also project two, five, and sometimes 10 years in advance. These long-term budgets are a key feature of the organization’s strategic planning process.

Strategic planning is the process whereby managers select the firm’s overall objectives and the tactics to achieve those objectives.

Strategic planning is primarily concerned with how the organization can add customer value and respond to competitors. For example, Air Canada is faced with the strategic question of how to respond to the environmental concerns related to air travel. Making this decision requires specialized knowledge of the various aircraft technologies and flight services on which Air Canada and other market participants compete, and knowledge of the future demand for air travel, along with consideration of potential regulatory changes to deal with global warming. At the operating level, the airline works to combine in-house programs with the greening of its supply chain to reduce waste, energy use, and noise, along with offering customers the option to purchase carbon offsets to reduce their carbon footprint. Air Canada has won numerous international awards for its leadership in eco-initiatives and its response to customer demands for green travel.

Long-term budgets, like short-term budgets, encourage managers with specialized knowledge to communicate their forecasts of future expected events. Such long-term budgets contain forecasts of large asset acquisitions (and financing plans) for the manufacturing and distribution systems required to implement the strategy. Research and development (R& D) budgets are long-term plans of the multi-year spending required to acquire and develop the technologies to implement the strategies.In short-term budgets, important estimates include the quantities produced and sold, and prices. All parts of the organization must accept these estimates. In long-term budgets, important assumptions involve the choice of markets to serve and the technologies to be acquired.

A typical firm integrates the short-term and long-term budgeting process into a single process. As next year’s budget is being developed, a five-year budget is also produced. The first year of the five-year plan is next year’s budget. The second and third years are fairly detailed, and the second becomes the base on which to establish next year’s one-year budget. The fourth and fifth years are less detailed, but incorporate new market opportunities. Each year, the five-year budget is rolled forward one year and the process begins anew.

The short-term (annual ) budget involves both planning and control functions, thus a trade-off arises between these two functions. Long-term budgets are rarely used as a control (performance evaluation) device because many of the managers who prepared the budget have either left the firm or are in new position. Instead, long-term budgets are used primarily for planning. Five-and ten-year budgets force managers to think about strategy and to communicate their specialized knowledge of potential future markets and technologies. Thus, long-term budgets have much less conflict between planning and control, since much less emphasis is placed on using the long-term budget as a performance-measurement tool.

Long-term budgets also reduce manager’s focus on short-term performance. Without long-term budgets, managers have an incentive to cut expenditures, such as maintenance, marketing, and R&D, in order to improve short-term performance. Alternatively, managers might seek to balance short-term budgets at the expense of the firm’s long-term viability. Budgets that span five years increase the likelihood that top management and/or the board of directors are informed of the long-term trade-offs that are being taken to accomplish short-term goals.

Some organizations and studies question the usefulness of budgets and the budgeting process in today’s global marketplace. Three approaches have been frequently adopted by firms. Rolling budgets rely on better forecasting to update budgets at regular intervals. Activity-based budgeting integrates activity-based costing into the budgeting and planning process. “Beyond budgeting” advocates alternatives to the annual budget process and employee incentives based on performance relative to that of competitors instead of budget attainment. Each approach has trade-offs with respect to planning and control.

Beyond budgeting shifts planning and control away from a reliance on the annual budget in conjunction with greater decentralization of decision making.

Much attention has been given to the relative success of these alternatives compared to traditional budgeting techniques. Statoil is one of many firms that have modified organizational strategy and structure to remain competitive in a rapidly changing market for energy and resources. In conjunction with its strategic and structural changes due to global growth, Statoil modified its accounting and management systems.

| Organizational Analysis | Statoil |

|---|

| Statoil, an international energy company headquartered in Norway, operates with approximately 25,000 employees in more than 40 countries. Statoil’s strategy is to meet the growing demand for energy while demonstrating due consideration for the environment, and efforts to fight global climate change through a value-based performance culture. The government of Norway holds two-thirds of the company shares, with the remainder held by private investors in Norway and other countries. Statoil is listed on both the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) and the Oslo Stock Exchange. Rapid changes in technology, market risk, and the growing demand for energy sources that are safe and sustainable have motivated Statoil to adapt not only its operations, but also its organizational structure. In a highly competitive industry subject to the impacts of global events and government policies, Statoil employs a dynamic management model emphasizing employee empowerment and efficient resource allocation. The annual budget has been replaced with a performance management system based on key performance indicators. Cost targets are used when deemed necessary and frequently replaced by event-driven analysis of costs trends. In parallel with its re-organization, Statoil changed its accounting system. It eliminated its use of annual budgets, replacing them with a system of forecasts and key performance indicators (KPIs) to meet its strategic objectives. The focus is an actions (who, what, how, and when) to achieve targeted outcomes and on revising actions to reflect new events and updated forecasts. The forecasts and KPIs such as new oil leases signed, carbon footprint, and cubic feet of natural gas delivered form the basis for performance evaluation of organizational units and individual employees, including internal and external benchmarking. |

Normally, accountants have the responsibility for presenting management’s budgeting goals in financial terms. In this role:

- They translate management’s plans and communicate the budget to employees throughout the company.

- They prepare periodic budget reports that provide the basis for measuring performance and comparing actual results with planned objectives.

The budget itself, and the administration of the budget, however, are entirely management responsibilities.

The Benefits of Budgeting

The primary benefits of budgeting are:

- It requires all levels of management to “plan ahead and to formalize goals on a recurring basis.

- It provides “definite objectives for evaluating performance at each level of responsibility.

- It creates an “early warning system for potential problems so that management can make changes before things get out of hand.

- It facilitates the “coordination of activities within the business. It does this by correlating the goals of each segment with overall company objectives. Thus, the company can integrate production and sales promotion with expected sales.

- It results in greater “management awareness of the entity’s overall operations and the impact on operations of external factors, such as economic trends.

- It “motivates personnel throughout the organization to meet planned objectives.

A budget is an aid to management; it is not a substitute for management. A budget cannot operate or enforce itself. Companies can realize the benefits of budgeting only when managers carefully administer budgets.

Essentials of Effective Budgeting

Effective budgeting depends on a “sound organizational structure. In such a structure, authority and responsibility for all phases of operations are clearly defined.

Budgets based on research and analysis should result in realistic goals that will contribute to the growth and profitability of a company. And, the effectiveness of a budget program is directly related to its acceptance by all levels of management.

Once adopted, the budget is an important tool for evaluating performance. Managers should systematically and periodically review variations between actual and expected results to determine their cause(s). However, individuals should not be held responsible for variations that are beyond their control.

Length of the Budget Period

The budget period is not necessarily one year in length. A budget may be prepared for any period of time. Various factors influence the length of the budget period. These factors include:

- the type of budget,

- the nature of the organization,

- the need for periodic appraisal, and

- prevailing business conditions. For example, cash may be budgeted monthly, whereas a plant expansion budget may cover a 10-year period.

The budget period should be long enough to provide an attainable goal under normal business conditions. Ideally, the time period should minimize the impact of seasonal or cyclical fluctuations. On the other hand, the budget period should not be so long that reliable estimates are impossible.

The most common budget period is one year. The annual budget, in turn, is often supplemented by monthly and quarterly budgets.

Many companies use continuous 12-month budgets. The budgets drop the month just ended and add a future month. One advantage of continuous budgeting is that it keeps management planning a full year ahead.

The Master Budget

The term budget is actually a shorthand term to describe a variety of budget documents. All of these documents are combined into a master budget.

The master budget is a set of interrelated budgets that constitutes a plan of action for a specific time period.

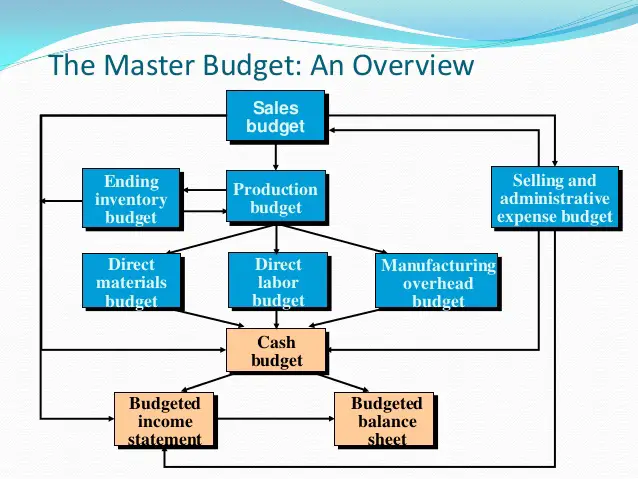

The master budget contains two classes of budgets:

- Operating budgets are the individual budgets that result in the preparation of the budgeted income statement. These budgets establish goals for the company’s sales and production personnel.

- Financial budgets, in contrast, are the capital expenditure budget, the cash budget, and the budgeted sheet.

These budgets focus primarily on the cash resources needed to fund expected operations and planned capital expenditures. Figure X-1 shows the individual budgets included in a master budget, and the sequence in which they are prepared.

Figure X-1. Master Budget. Credit: SlideShare.

Figure X-1. Master Budget. Credit: SlideShare.

The organization first develops the operating budgets, beginning with the sales budget. Then it prepares the financial budgets. These budgets are important to discuss, however, they are beyond the scope of this literature.

You Might Also Like:

- Research data for this work have been adapted from the manual:

- Managerial Accounting: Tools for Business Decision Making By Jerry J. Weygandt, Paul D. Kimmel, Donald E. Kieso