Divisional Structure

Divisional structure is a fundamentally different way of organizing by which members of the organization are grouped on the basis of products, services, customers, or geography.

The divisional structure (also called an M-form (multidivisional) or a decentralized structure) is a form of organizing by which organizational members are organized with responsibility for designated products, services, product groups, major projects or profit centers.

Thus, an organization structured within the framework of divisional structure has its activities designed based on common products or services, target customers, or geographic market.

This structure is sometimes called a product structure or strategic business unit structure. The distinctive feature of a divisional structure is that grouping is based on organizational outputs. For example, LEGO GroupOpens in new window shifted from a functional structure to a divisional structure with three product divisions:

- DUPLO, with its big bricks for the youngest children;

- LEGO construction toys; and

- a third category for other forms of LEGO play materials such as buildable jewelry.

Each division contained the functional departments necessary for that toy line.

The defunct United Technologies Corporation (UTC), which was among the 50 largest U.S. industrial firms, had numerous divisions, including

- Carrier (air conditioners and heating),

- Otis (elevators and escalators),

- Pratt & Whitney (aircraft engines), and

- Collins Aerospace (technology products for the aerospace and defense industries).

The Chinese online-commerce company TaobaoOpens in new window, which is a division of Alibaba GroupOpens in new window, is further separated into three divisions that provide three different types of services:

- linking individual buyers and sellers;

- a marketplace for retailers to sell to consumers; and

- a service for people to search across Chinese shopping websites.

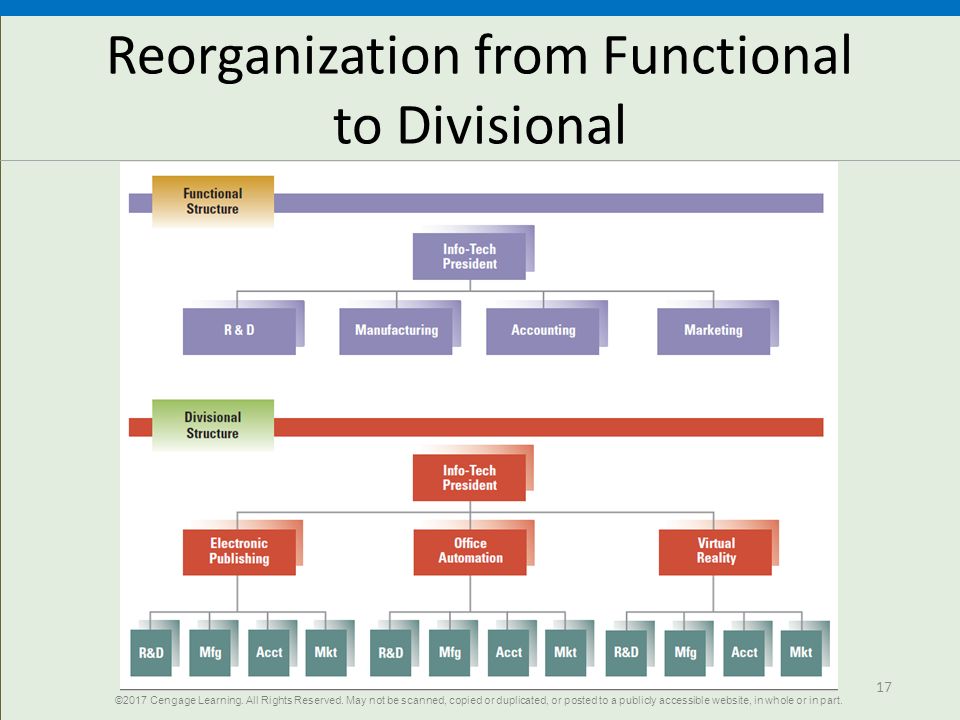

OrganizationsOpens in new window tend to shift from functional to divisional structures as they become more complex. The difference between a divisional structure and a functional structure is illustrated in Figure X-1.

Figure X-1 Reorganization from Functional to Divisional Structure | Credit — Slide Player Opens in new window

Figure X-1 Reorganization from Functional to Divisional Structure | Credit — Slide Player Opens in new window

|

The functional structureOpens in new window can be redesigned into separate product groups, and each group contains the functional departments of research and design (R&D), manufacturing, accounting, and marketing. Coordination is maximized across functional departments within each product group.

The divisional structure promotes flexibility and change because each unit is smaller and can adapt to the needs of its environment.

Moreover, the divisional structure decentralizes decision making because the lines of authority converge at a lower level in the hierarchy. The functional structureOpens in new window, by contrast, is centralized because it forces decisions all the way to the top before a problem affecting several functions can be resolved.

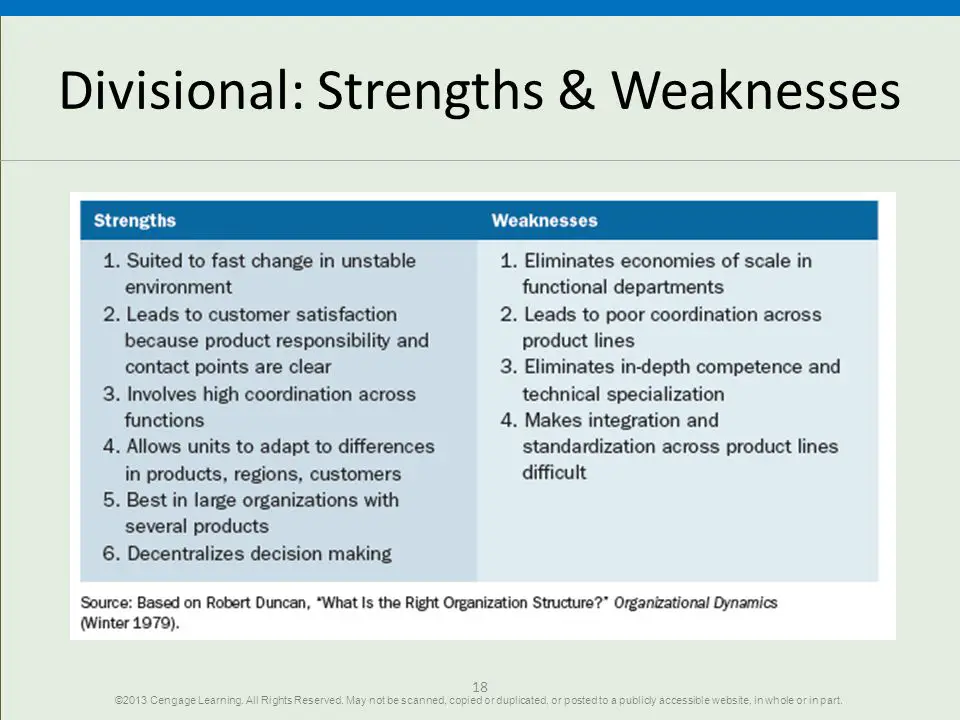

Strengths and weaknesses of the divisional structure are summarized in Figure X-2.

Figure X-2 Strengths and Weaknesses of Divisional Structure | Credit — Slide Player Opens in new window

Figure X-2 Strengths and Weaknesses of Divisional Structure | Credit — Slide Player Opens in new window

The divisional organization structure is excellent for achieving coordination across functional departments. It works well when organizations can no longer be adequately controlled through the traditional vertical hierarchy and when goals are oriented toward adaptation and change.

When Google grew from a small search engine into a giant company operating in areas as diverse as biotechnology and finance, co-founder and CEO Larry Page reorganized into a type of divisional structure to keep adaptation and innovation a thriving part of all the businesses.

| IN PRACTICE | Google and Alphabet |

|---|

| Google was founded as a company that did Internet search. Yet by 2015, it was involved in everything from pharmaceuticals to self-driving cars. Google’s then-CEO Larry Page and his co-founder Sergey Brin decided to restructure the various businesses under a new parent company, called Alphabet, to give managers in the businesses more autonomy and keep the companies innovative and adaptable. The largest division of Alphabet is Google, which includes the traditional business of search and advertising along with other activities. Other divisions include Verily, a life-science research organization; self-driving car unit Waymo; CapitalG, which provides late stage venture capital funding; and X Development, which focuses on various experimental products and services. Each business unit has its own goals and budget, each contains all the functions needed to perform its tasks, and each has its own CEO and management team. Management style and culture may also vary among the divisions. For instance, although Google offers napping pods for employees, not all divisions of Alphabet follow suit. The idea behind Alphabet is that by being smaller and more independent, each unit can be nimbler and more innovative to serve the fast-moving needs and desires of customers. “There can be a lot of cross-company confusion when companies get too big, and this will allow people to build the right set of products for the right users …” said Wesley Chan, a Google veteran who is now a partner at venture capital firm Felicis Ventures. |

Google co-founders Page and Brin serve as CEO and President of Alphabet. Page says the structure will continue to evolve. Many companies find that they need to restructure every few years as they grow larger.

Giant, complex organizations such as General ElectricOpens in new window and Johnson & JohnsonOpens in new window are subdivided into a series of smaller, self-contained organizations for better control and coordination. In these large, complex companies, the units are sometimes called divisions, businesses, or strategic business units.

Johnson & JohnsonOpens in new window is organized into three major divisions: Consumer Products, Medical Devices and Diagnostics, and Pharmaceuticals, yet within those three major divisions are more than 250 separate operating units in 57 countries.

Some U.S. government organizations also use a divisional structure to better serve the public. One example is the Internal Revenue ServiceOpens in new window, which wanted to be more customer oriented.

The agency shifted its focus to informing, educating, and serving the public through four separate divisions serving distinct taxpayer groups—individual taxpayers, small businesses, large businesses, tax-exempt organizations. Each division has its own budget, personnel, policies, and planning staffs that are focused on what is best for each particular taxpayer segment.

The divisional structure has several strengths and is suited to fast change in an unstable environmentOpens in new window and provides high product or service visibility.

Since each product line has its own separate division, customers are able to contact the correct division and achieve satisfaction. Coordination across functions is excellent. Each product or service can adapt to requirements of individual customers or regions.

The divisional structure typically works best in organizations that have multiple products or services and enough personnel to staff separate functional units. Decision making is pushed down to the divisions. Each division is small enough to be quick on its feet, responding rapidly to changes in the market.

VerizonOpens in new window reorganized into three divisions serving different types of customers—Verizon Consumer Group, Verizon Business Group, and Verizon Media Group—to better respond to changing customer needs.

One disadvantage of using divisional structuring is that the organization loses economies of scale.

Instead of 50 research engineers sharing a common facility in a functional structure, 10 engineers may be assigned to each of five product divisions. The critical mass required for in-depth research is lost, and physical facilities have to be duplicated for each product line.

Another problem is that product lines become separate from each other, and coordination across product lines can be difficult. As a Johnson & Johnson executive once said, “We have to keep reminding ourselves that we work for the same corporation.”

Some companies that have a large number of divisions have had real problems with cross-unit coordination. Sony lost the digital music player business to Apple partly because of poor coordination. With the introduction of the iPod, Apple quickly captured 60 percent of the U.S. market versus 10 percent for Sony.

The digital music business depends on seamless coordination. Sony’s Walkman did not even recognize some of the music sets that could be made with the company’s SonicStage software and thus didn’t mesh well with the division selling music downloads.

Unless effective horizontal mechanisms are in place, a divisional structure can hurt overall performance. One division may produce products or programs that are incompatible with products sold by another division, as at Sony. Customers can become frustrated when a sales representative from one division is unaware of developments in other divisions.

Task forces and other horizontal linkage devicesOpens in new window are needed to coordinate across divisions. A lack of technical specialization is also a problem in a divisional structure. Employees identify with the product line rather than with a functional specialty. R&D personnel, for example, tend to do applied research to benefit the product line rather than basic research to benefit the entire organization.

The problem of coordination and collaboration is amplified in the international arena because organizational units are differentiated not only by goals and work activities, but also by geographical distance, time difference, cultural values, and perhaps language.

How can managers ensure that needed coordination and collaboration will take place in their company, both domestically and globally? Coordination is the outcome of information and cooperation. Managers can design systems and structures to promote horizontal coordination and collaborationOpens in new window.

The Series:

- Organization Structures Opens in new window

- Functional Structure Opens in new window

- Divisional Structure Opens in new window

- Matrix Structure Opens in new window

- Geographical Structure Opens in new window

- Virtual Network Structure and Outsourcing Opens in new window

- Holacracy Team Structure Opens in new window

- Adhocracy Opens in new window

- Research data for this work have been adapted from the manual:

- Organization Theory & Design By Richard L. Daft