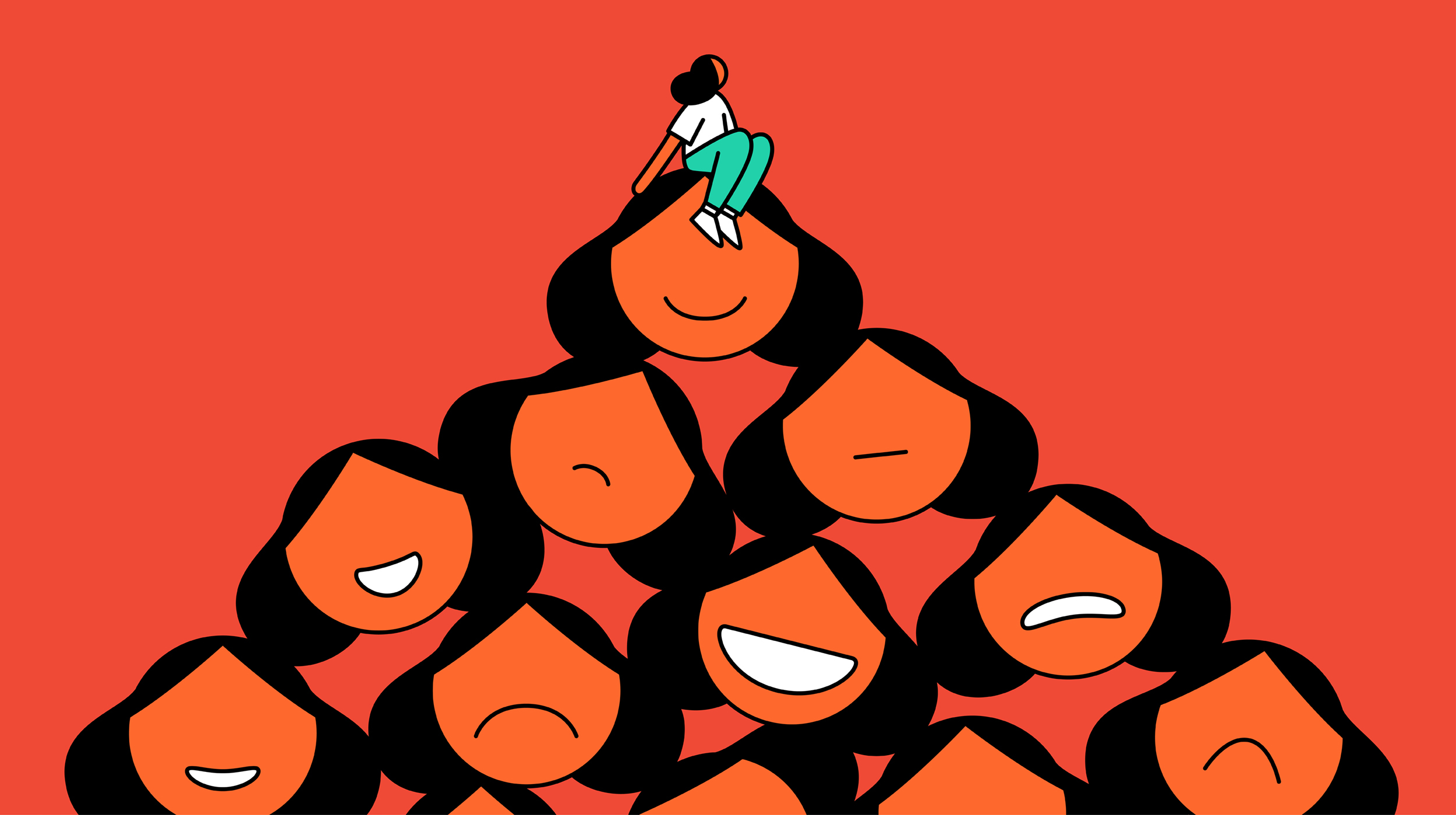

Narcissism

Understanding the Narcissistic Personality Disorder

Graphics courtesy of NBC NewsOpens in new window

Graphics courtesy of NBC NewsOpens in new window

|

Narcissistic personality disorder is characterized by a pervasive pattern of grandiosity, lack of empathy, a need for admiration, and hypersensitivity to evaluation of others.

Persons with narcissistic personality disorder

- have a grandiose sense of self-importance

- are preoccupied with fantasies of unlimited success and power

- tend to associate with high-status people

- have a sense of entitlement (feel entitled to get what they want when they want it), and are exploitative.

These set of people lack humility, are overly self-centered, have tendency to exploit others to fulfill their own desires, feel superior and entitled to special rights and privileges, and have little insight into inappropriate or objectionable behaviors — these individuals tend to have little insight into their own narcissism. They are often envious of others and show arrogant, haughty behaviors or attitudes.

Narcissists have an exaggerated sense of entitlement and believe that they deserve special treatment. They expect to receive love and admiration but have little empathy for others. Narcissistic individuals are often irritating, haughty, or difficult. Although they can appear outwardly charming, relationships tend to be superficial and cold.

| Table X-1. DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria for Narcissistic Personality Disorder |

|---|

A pervasive pattern of grandiosity (in fantasy or behavior), need for admiration, and lack of empathy, beginning by early adulthood and present in a variety of contexts, as indicated by five (or more) of the following:

|

Term and Derivation: How It All Started.

The legend of Narcissus, originally sung as Homeric hymns in the seventh or eighth century BC (Hamilton, 1942) and popularized in Ovid’s Metamorphoses (8/1958), has risen from a relatively obscure beginning to become one the prototypical myths of our times, with the coining of such terms as culture of narcissism, me generation (Lasch, 1979; Wolfe, 1976, 1977), and more recently the age of entitlement (Twenge & Campbell, 2009).

To paraphrase Ovid’s rendering of the Greco-Roman fable, Narcissus was a youth admired by all for his beauty. He rejected the attention of the many who adored him, including the nymph Echo, who by punishment of Zeus’ wife Hera, could only repeat the last syllable of speech said to her.

Ignored by Narcissus, Echo eventually wasted away until all that remained of her was her repeating voice.

Narcissus’ cruelty was eventually punished when an avenging goddess, Nemesis, answered the prayer of another he had scorned. She condemned him to unrequited love, just as he had done to the many he had spurned (both males and females, in Ovid’s telling).

Catching a glimpse of himself in a pool of water, Narcissus was paralyzed by the beauty of his own reflected image. The more he gazed at himself, the more infatuated he became, but like the many others whose affection he did not return, he was left empty in his futile love. He remained gazing at his own reflection in despair until death, with Echo by his side to repeat to him his last dying words.

Diagnosis

As earlier stated, persons with narcissistic personality disorder typically have an aggrandized sense of self-importance, overestimate their abilities, and inflate their accomplishments.

They expect to be recognized as superior, special, or unique. Patients are often preoccupied with fantasies that confirm and support their grandiosity; these fantasies often involve admiration and special privileges they believe should be forthcoming.

Their sense of entitlement may be exhibited by behaviors that demonstrate their expectation of special treatment, such as assuming they should not have to wait in line while others should.

They generally lack the ability to empathize with the desires, experiences, and feelings of others, and have an unemotional style of interpersonal involvement.

Patients with narcissistic personality disorder typically have vulnerable self-esteem, which makes them particularly sensitive to injury from criticism, defeat, and rejection. Their interpersonal relationships are inevitably impaired because of problems derived from their feelings of entitlement, need for admiration, and disregard for the sensitivities of others.

Pathogenesis

Temperaments characterized by high energy, tension, and conscientiousness may nonspecifically predispose persons to the disorder. Some theories suggest that pathological narcissism develops from ongoing childhood experiences of having fears, failures, or other signs of vulnerability responded to with criticism, disdain, or neglect.

Epidemiology

Narcissistic personality disorder has been considered uncommon. Although one survey reported a prevalence of approximately 6%, it is estimated that the prevalence of narcissistic personality disorder in the general population is less than 1 percent. The disorder is diagnosed in men more frequently than in women.

Viewed as stable over time, research suggests that the disorder can vary under the influence of significant life events, such as achievement and new relationships. When these individuals seek help, it is likely for the anger or depression they feel when deprived of something to which they feel entitled, such as a promotion. This is sometimes referred to as a narcissistic injury.

The following vignette illustrates many of the symptoms of narcissistic personality disorder:

| Dr. Smith, a 53-year-old physician, was known for having an expansive and grandiose attitude for belittling colleagues’ accomplishments. While seeking the admiration and adulation of others, he rarely reciprocated, displaying superficial charm without a genuine capacity for empathy. His nurse said, “When you talk to him, it’s like you’re not even really there as a person. It’s like he can’t connect.” Dr. Smith’s sense of entitlement led him to bill Medicare and other insurance carriers for services that he had never provided or that were inflated on the bills. He believed that he was entitled to a higher level of payment because of his training, experience and keen intelligence. At the urging of his colleagues, and after being repeatedly caught and confronted about his billing fraud, Dr. Smith entered therapy with a well-known psychoanalyst, Dr. Brown. Months into therapy, Dr. Smith told a colleague: “I think Dr. Brown envies me; he knows how much money I make. I can tell my success bothers him.” Dr. Smith eventually was investigated, indicted on multiple criminal fraud counts, and prosecuted in federal court. Many colleagues testified against him. “I can’t believe they would do this to me,” he was heard to say. Convicted on all counts, Dr. Smith was sentenced to 5 years in prison. |

Treatment

Individual psychotherapy is the basic treatment for patients with narcissistic personality disorder. There is considerable variability in the course of the disorder. Most patients show improvement in their occupational adjustments and interpersonal relationships over time.

The Rise of Interest in Narcissism

Kernberg’s and Kohut’s writings on narcissism were, in part, a reaction to increased clinical recognition of these patients. Their papers stimulated enormous worldwide interest about the nature of narcissism and how it should best be conceptualized and treated.

In Kernberg’s view, narcissism develops as a consequence of parental rejection, devaluation, and an emotionally invalidating environment in which parents are inconsistent in their investment in their children or neglect interaction with their children to satisfy their own needs.

For example, at times a parent may be cold, dismissive, and neglectful of a child, and then at other times, when it suits the parent’s needs, be attentive and even intrusive.

This parental devaluation hypothesis states that because of cold and rejecting parents, the child defensively withdraws and forms a pathologically grandiose self-representation. This self-representation, which combines aspects of the real child, the fantasized aspects of what the child wants to be, and the fantasized aspects of an ideal, loving parent, serves as an internal refuge from the experience of the early environment as harsh and depriving.

The negative self-representation of the child is disavowed and not integrated into the grandiose representation, which is the seat of agency from which the narcissist operates. This split-off unacceptable self-representation can be seen in the emptiness, chronic hunger for admiration and excitement, and shame that also characterize the narcissist’s experience (Akhtar & Thompson, 1982).

What Kernberg sees as defensive and compensatory in the establishment of the narcissist’s grandiose self-representation, Kohut (1971, 1977) views as a normal development process gone awry. Kohut sees pathological narcissism as resulting from failure to idealized the parents because of rejection or indifference.

For Kohut, childhood grandiosity is normal and can be understood as a process by which the child attempts to identify with and become like his idealized parental figures. The child hopes to be admired by taking on attributes of perceived competence and power that he or she admires in others.

In normal development, this early grandiose self eventually contributes to an integrated, vibrant sense of self, complete with realistic ambitions and goals. However, if this grandiose self is not properly modulated, what follows is the failure of the grandiose self to be integrated into the person’s whole personality.

According to Kohut, as an adult, a person with narcissism rigidly relates to others in “archaic” ways that befit a person in the early stages of proper self-development.

Others are taken as extensions of the self (Kohut’s term is selfobject) and are relied on to regulate one’s self-esteemOpens in new window and anxieties regarding a stable identity.

Because narcissists are unable to sufficiently manage the normal fluctuations of daily life and its effective correlates, other people are unwittingly relegated to roles of providing internal regulation for them (by way of unconditional support admiration and total empathic attunement), the same way a parent would provide internal regulation for a young child.

Although Kohut and Kernberg disagreed on the etiology and treatment of narcissism, they agreed on much of its phenomenology or expression, particularly for those patients in the healthier range.

Both these authors have been influential in shaping the concept of narcissistic personality disorder, not only among psychoanalysts but also among contemporary personality researchers and theorist and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of the American Psychiatric Association, for discussion of the development of DSM’s concept of narcissistic personality disorder.

You Might Also Like:

- Cooper, A., & Ronningstam, E. (1992). Narcissistic personality disorder. In A. Tasman & M. B. Riba (Eds.), American psychiatric press review of psychiatry (Vol. 11). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press.

- Davies, M. L. (1989). History as narcissism. Journal of European Studies, 19, 265 – 291.

- Dickinson, K. A., & Pincus, A. L. (2003). Interpersonal analysis of grandiose and vulnerable narcissism. Journal of Personality Disorders, 17, 188 – 207.

- Ellis, H. (1927). The conception of narcissism. Psychoanalytic Review, 14, 129 – 153.

- Emmons, R. A. (1981). Relationship between narcissism and sensation seeking. Psychological Reports, 48, 247 – 250.

- Emmons, R. A. (1984). Factor analysis and construct validity of the narcissistic personality inventory. Journal of Personality Assessment, 48, 291 – 300.

- Gramzow, R., & Tagney, J. P. (1992). Proneness to shame and the narcissistic personality. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 18 (3), 369 – 376.

- Gunderson, J. G., Ronningstam, E., & Smith L. E., & Smith L. E. (1991). Narcissistic personality disorder: A review of data on DSM-III-R descriptions. Journal of Personality Disorders, 5, 167 – 178.

- Hendin, H. M., & Cheek, J. M. (1997). Assessing hypersensitive narcissism: A reexamination of Murray’s narcissism scale. Journal of Research in Personality, 31 588 – 599.