Language

Language: Acquiring the Language Skill

The term language refers to a system of communication consisting of symbols—words or hand signs (as in the case of American Sign Language)—arranged according to a set of rules, called a grammar, to express meaning (Gertner, Fisher, & Eisengart, 2006).

At its simplest, Language is a system of communication composed of symbols (words, hand signs, etc.) that are arranged according to a set of rules (grammar) to form meaningful expressions.

Grammar, by the way, is a set of rules governing how symbols in a given language are used to form meaningful expressions.

It is scarcely possible to imagine life without language. Chances are that if you find two or more people together anywhere on earth they will soon be exchanging words. When there is no one to talk with, people talk to themselves, to their dogs, even to their plants.Steven Pinker (1994)

The ability to use language is a remarkable cognitive ability Opens in new window so tightly woven into the human experience, says prominent linguist Steven Pinker (1994), that “it is scarcely possible to imagine life without it. Chances are that if you find two or more people together anywhere on earth they will soon be exchanging words. When there is no one to talk with, people talk to themselves, to their dogs, even to their plants.”

In this literature, we'll examine the remarkable capacity of humans to communicate through language, and consider the basic components of language, developmental, milestones in language acquisition, and leading theories of language acquisition. We also consider the question of whether language is a uniquely human characteristic.

Components of Language

As we’ll see, language consists of four basic components:

- phonemes,

- morphemes,

- syntax, and

- semantics.

Phonemes are the basic units of sound in a spoken language. English has about 40 phonemes to sound out the 500,000 or so words found in modern unabridged English dictionaries. The word dog consists of three phonemes: “d,” “au,” and “g.”

Phonemes in English correspond both to individual letters and to letter combinations, including the “au” in dog and the sounds “th” and “sh.” The same letter can make different sounds in different words. The “o” in the word two is a different phoneme from the “o” in the word one. Changing one phoneme in a word can change the meaning of the word. Changing the ‘r” sound in reach to the “t” sound makes it teach.

Different languages have different phonemes. In some African languages, various clicking sounds are phonemes. Hebrew has a guttural “chhh” phoneme, as in the expression l’chaim (“to life”).

Phonemes are combined to form morphemes, the smallest units of meaning in a language. Simple words such as car, ball, and time are morphemes Opens in new window, but so are other linguistic units that convey meaning, such as prefixes Opens in new window and suffixes Opens in new window. The prefix “un,” for example, means “not.” The suffix “ed” following a verb means that the action expressed by the verb occurred in the past. More complex words are composed of several morphemes. The word protested consists of three morphemes: “pre,” “test,” and “ed.” Language requires more than phonemes and morphemes. It also requires syntax, the rules of grammar that determine how words are ordered within sentences and phrases to form meaningful expressions, and semantics, the set of rules governing the meaning of words. The sentence “buy milk I” sounds odd to us because it violates a basic rule of English syntax—that the subject (“I”) must precede the verb (“buy”). We follow rules of syntax in everyday speech even if we are not aware of them or cannot verbalize them. But even when our speech follows proper syntax, it may still lack meaning. The famed linguist Noam Chomsky, illustrated this point with the example “Colorless green ideas sleep furiously.” The sentence may sound correct to our ears since if follows the rules of English syntax, but it doesn’t convey any meaning. The same word may convey very different meanings depending on the context in which it is used. “Don’t trip going down the stairs” means something very different from “Have a good trip.”

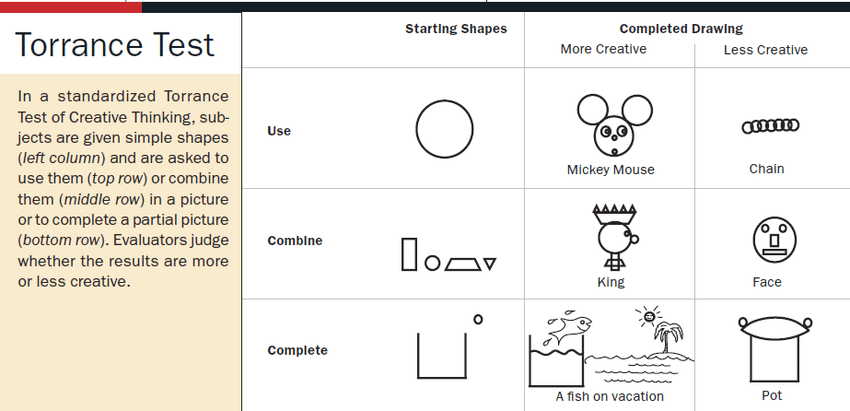

Figure X2 shows another way of measuring creative thinking, which is based on judging the creativity of a person’s drawings. When we think creatively, we use cognitive processes to manipulate or act on stored knowledge.

Figure X2 Torrance Test of Creative Thinking

|

| Figure X2 Torrance Test of Creative Thinking | In the Torrance Test, subjects are given starting shapes (left column) and instructed to create a new drawing by using them (top row), combining them (middle row), or completing them (bottom row). Evaluators then judge the creativity of the completed drawings. Source: Courtesy of ResearchGate Opens in new window |

Investigators identify a number of cognitive processes that underlie creative thinking, including the use of metaphor and analogy, conceptual combination, and conceptual expansion (Ward, 2004, 2007; Ward, Smith, & Vaid, 1997/2001).

- Metaphor and Analogy

Metaphor and analogy are creative products in their own right; they are also devices we use to generate creative solutions to puzzling problems. A metaphor Opens in new window is a figure of speech Opens in new window for likening one object or concept to another. Applying a metaphor involves a creative process of thinking of one thing as if it were another. For example, we might describe love as a candle burning brightly.

Analogy, of course, is a comparison between two things based on their similar features of properties—for example, likening the actions of the heart to those of a pump. As we noted, Alexander Graham Bell showed creative use of analogy Opens in new window in his invention of the telephone.

- Conceptual Combination

Cognitive psychologists believe combining two or more concepts into one can result in a novel ideas or applications that reflect more than the sum of the parts (Costello & Keane, 2001). Example of conceptual combinations include “cell phone,” “veggie burger,” and “home page.” Can you think of other ways in which concept can be creatively combined?

- Conceptual Expansion

One way of developing novel ideas is to expand familiar concepts Opens in new window. Examples of conceptual expansion include an architect’s adaptation of an existing building to a new use, a writer’s creation of new scenes using familiar characters, and a chef’s variation on a traditional dish that results in a new culinary sensation.

Creativity typically springs from the expansion or modification of familiar categories or concepts. The ability to take what we know and modify and expand on it is one of the basic processes of creative thinking.

related literatures:

- Jeffrey S. Nevid, Psychology: Concepts and Applications. (p. 260-1) Creativity: Not Just for the Few